In this post I discussed what “Encounters” meant in 1970s RPGs.

I later came across this post at Dispatches from Kickassistan called Dynamic Hexcrawl Required Reading: Yoon-Suin & Philosophy.

While the post is primarily about Yoon-Suin‘s amazing tables and design philosophy for presenting an RPG setting, it also addresses the value of randomization and tables in general.

I believe that such syntactical weight should be given to the improvisation, innovation and creation processes. Charts and tables can give you elements to play with, but it is through a conscious, creative action of building interrelations between those elements that details become facts and that facts are given life at the game table. We must interpret the data given to us and it is in that act of interpretation that data-gathering becomes synthesis, where we create something new out of the raw “A, B, C” of our data source.

This is why I love tables.

The best things that tables can be are (a) inventive (introducing new things I might not have thought about otherwise) and (b) useful. Yoon-Suin’s tables do these things on nearly every page. The book focuses more on creating interesting and useful social structures than stuff like terrain and lairs because, let’s face it, there’s enough stuff out there in other resources (or already in our brains) that reinventing the wheel isn’t always the most practical thing an author can do. But what is practical? Taking the “here, make it yourself” a few steps further than I’ve seen it done before and instead of telling me “this kingdom is like this, this other kingdom is like that,” author David McGrogan gives us different series of tables to let us figure out for ourselves what each place is like. In essence, he provides an aesthetic, you and I fill in the blanks when set about using the material. He provides the words, you and I supply the syntax.

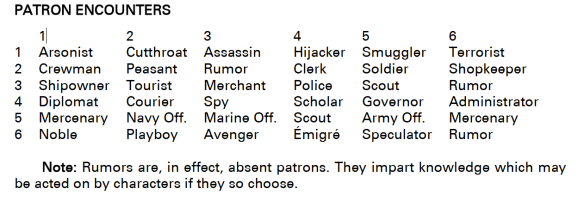

One only has to keep the logic of this post in mind and see the value of Classic Traveller’s Main World Generation system and the use of its Random Encounter Tables. (Traveller‘s random encounter tables range from NPCs, to Patrons, to Starship Encounters, to Legal Encounters, to Animals.)

I should add that the Kickassistan post and posts like it are a corrective to folks who say, “I don’t like the crazy worlds Traveller‘s Main World Generation system offers.”

Tk Ben fair, the people who complain about the results of the Main World Generation System are usually the folks trying to map entire an Traveller sector. That’s 16 subsectors, which averages 560 worlds! And sometimes they are trying to map multiple sectors(!), so drilling down for imaginative gold for so many planets might well prove frustrating if not impossible.

But if one remembers that in original Traveller one was supposed to develop one, maybe two, subsectors, the use of randomly generated Main Worlds as “a prod to the imagination” makes perfect sense. The system produces results that demand extraordinary justifications–and thus settings worthy of pulp adventure science-fiction.

I think expanding the Random Patron table in Classic Traveller with some lessons from Yoon-Suin might be interesting.

Here are example tables from Yoon-Suin. In these tables the Referee determines what group the Player Characters encounter or know:

One of the results is 6. Noble House.

Here is the table for Noble House:

One could create such tables for a world, a cluster of stars or a subsector, to create a specific feel of culture and place. Many elements on the tables could be design as “open sets,” so instead of “Nobility” it might be “Ruling Class”–a term translatable to any kind of government system or world culture.

For something far less involved one could expand on the Traveller Patron Encounter table, modeling it on this table from Yoon-Suin:

In this case, one would roll on the Patron Encounter from Classic Traveller, then roll on the middle column above, and then once more on the Classic Traveller Patron Encounter table. In this way the Referee doesn’t find himself simply staring at a noun (“Arsonist”). Instead, the table helps prompt action and situation in the Referee’s imagination.

Also note that in this method which NPC is looking to hire the PCs is not specified. The Referee, once he brainstorms up the situation, is free to have any of the NPCs he concocts wth this method approach the NPCs. An Arsonist might be the first NPC rolled, but it might be the Noble who hires the NPCs, knowing their is an Arsonist on his tail.

APPLYING THIS TO TRAVELLER

Over at Citizens of the Imperium (membership required to read threads past the first post), Mike Wightman wrote up another interesting method of using the Patron Encounter table to help generate interesting results:

Easiest way is with an example (note that this is using the 81 version of LBB3 – Starter Edition and The Traveller Book actually have much more comprehensive tables)

I roll on the patron table and get:

rumour, avenger, army

next I roll on random person encounter

workers, animal encounter (a roll of 6,n I take as animal or alien) and ambushing brigands.

I pick the starting encounter:

Lets say the players encounter some workers who are obviously agitated, discussion with them reveals that the industrial plant they have been operating has been closed due to rumours of some violent native beast, and that some hotheads are thinking of going to hunt the animals down. There is a rumour that the animals in question have highly valuable (insert whatever you want here – anagathic glands, valuable fur, expensive blubber – whatever).

Players may or may not join the hunt, but they have been seen talking to the workers.

Next encounter depends – if they go on the animal hunt then they may encounter the ambushing brigands who are also after the animals, or they may encounter the army patrol guarding the industrial site and containing the animals.

If they don’t go on the hunt they are approached by the avenger who has lost (family member, best friend, whatever will pull players in) and offers to guide the players past the workers/army guards to get to the animals.

If they went along with the workers they may still encounter the avenger being attacked by the brigands/army patrol.

It’s fairly organic – I may decide to change the encounter order in response to player actions, and reaction rolls may make things more tense than they need to be.

And at some point I have to generate the animal stats…

By making several rolls on the Patron Encounter table, and letting his brain mull how they might be connected, he creates situations (not a linear adventure) for the Player Characters to wander into.

This kind of thinking–create situations for the Player Characters to wander into through the use of random tables–is often poo-pooed these days. But it was the bread-and-butter of RPG play in the 1970s.

The shift occurred when the model of publishing changed. At first, games were self-contained, with tables offering Referees and players a toolset method for creating situation, setting, and play. When you bought OD&D or Original Traveller, you really didn’t need anything else to have countless hours of play.

But, of course, that led the creators of these games with nothing else to sell. Moreover, consumers, being consumers, wanted to buy more things. Publishers obliged the consumers by creating detailed setting and pre-built adventures.

BACK IN THE OLD DAYS: SITUATIONS, NOT PRE-PLOTTED STORIES

BACK IN THE OLD DAYS: SITUATIONS, NOT PRE-PLOTTED STORIES

A distinction has to be made here. The early adventures of Dungeons & Dragons were environments. That is, they had no plot and were not linear in their expectation of play. They were situations scattered around a map. What the Player Characters chose to pursue, in what order, whether to fight them, outsmart them, avoid them, exploit them, were all matters left to the Players to decide for their Player Characters.

So, as a modern example, I ran the module Death Frost Doom from Lamentations of the Flame Princess. (You can read all about my LotFP campaign if you are so interested.)

[SOME SPOILERS ABOUT DFD FOLLOW BELOW!!!]

The module is a terrific dungeon scenario. But it is structured in an interesting way:

The quest-item the PCs seek is at a “chock-point” in the geography of the dungeon, which basically divides the dungeon in half, and thus the adventure. The Players, upon having their characters find the quest object, can elect to grab the object and get the hell out of the creepy place. Or they can continue on, dealing deeper into the weirdness.

Importantly, the second half of the dungeon is where things get particularly bat-shit crazy. Even more importantly, there are events waiting in that back-back have what can have a cataclysmic, apocalyptic effect on the game’s campaign setting.

I ran the scenario knowing of two things would happen: An undead priest ruling an army of thousand of undead would rise and march on 17th Century Europe — or he would not. That, clearly, is a big fork in the road for any campaign. And I played it without any concern or expectation as to which way it would go. The Players would make choices and take actions on behalf of their PCs… and the fallout of those choices would dictate the direction of the campaign. I had no big plot, no agenda, no “right way” I wanted the “story” to go. I had no story, I had no expectations for the campaign. The campaign would, in fact, be exactly what it turned out to be, found through play, not in planning.

BACK TO TRAVELLER

If one reads the Adventure 1: The Kinunir for Classic Traveller one finds four situations, not a “story” or a campaign of any kind. The book is basically a list of suggestions for scenarios that the Referee will have to flesh out. Adventure 1 does not assume any sort of straightforward plot. Rather, Adventure 1 assumes the Referee will be using both the material contained within its pages and all the Random Encounters Tables found in Traveller Books 1-3. These tables would be used to flesh out situations and an evening of play, adding unexpected details and situations and filling out the environment in unexpected ways.

But module design would change drastically within the first few years of the hobby.

By 1980 what I think of as “Old School” was already shifting and becoming lost. The needs of publishers are in many ways the antithetical to the promise of the early years of the hobby. Call of Cthulhu, for example, published in 1981, was firmly in the camp of very linear, very “Your Players Will Experience This” modules.

I don’t think the folks first playing D&D from 1974 to, say, 1978 would ever have imagined such a structure as the Dragonlance modules. And, I would argue, the folks first playing Traveller would have looked at The Traveller Adventure and not quite known what to make of it.

Many people enjoy these very plotted adventures–and I would never begrudge those people their pleasure. My only point is that such designs gut the original spirit of play of early RPGs.

Tightly structured adventure scenarios fall apart with too much randomness or too much freewheeling agency on the part of the PCs. Rather than find out where the campaign goes based on the mix of the PCs actions and randomly rolled details, later RPG design expected PCs to follow the paths of the adventure “correctly”–or render the investment of the module useless. Whether such play is better or worse, it is certainly different.

One of the joys of the OSR is bringing back a trust and expectation of randomness, and a love of discovering where the campaign will go through play.

I suspect the reason Call of Cthulhu, the original Star Wars and Star Trek RPGs, and other high points of the early Eighties boom were story-focused rather than what we now call “Sandbox” style can also be attributed to their source material. All of the licensed games were based on works of fiction — which is to say, stories. Sure, you could run a game based on random encounters at Mos Eisley or exploring Innsmouth to see what you find, but those things wouldn’t feel like Star Wars or Lovecraft.

Whereas I think one reason there has never been a very successful Conan RPG is that Conan’s adventures always did feel like random encounters in an exotic and colorful sandbox. You don’t really need a sourcebook for that.

This in turn leads to the obvious conclusion that (as Kipling tells us) there is no One True Way to do roleplaying. I’m very glad to see the revival of “old school” gaming and the investigations of what the original games were supposed to do and why; certainly my own games have benefited from reading Yoon-Suin and your own Traveller series. But it’s worth remembering that there are other games based on reproducing the experience of a story, which naturally require a more structured situation or series of events.

I think that’s all solid stuff. Particularly the notion that once licensing began, the *point* of play was to recreate structured story. Before that, there was a thing called RPGs that were inspired by many storied.

A point I want to make:

I’ll be up front: I don’t like “plotted” scenarios for RPGs. I think they take the spirit and fun away from what RPGs, as a medium, are about.

With that said, although these blog posts are about OSR games and game-play, here are some of the other games I love:

Sorcerer

Primetime Adventures

Burning Wheel Gold

Each of these games is built on long-form, character-enteric storytelling, where beliefs, morals, character issues are the focus of play. That is to say, I’m not a One True Way kind of guy. Never have been. Never will be.

The fact that I drill down into specific methods of play doesn’t mean I am saying those methods are the only ways or the right ways to play RPGs — even for me. Even the ways of playing I don’t enjoy (pre-plotted scenario play, for example), is something I know some folks like. And if that is what they like, more power to them.

I think there’s some room though in Burning Wheel for random tables to inspire a GM in creating situations and coming up with failure consequences, so the ideas from 1970’s play are not completely useless to play of more recent games.

You’re absolutely right. If the Referee creates a world, builds tables to help reflect that world, he can use them to mix and match ideas as presented above to come up with situations and encounters he might not have otherwise thought of.

Here’s an interesting blog post along these lines:

https://geekken.wordpress.com/2016/08/09/random-sci-fi-adventure-generator/

Some great observations, thanks for sharing!

Pingback: Fallen World Campaign [LotFP]–Twenty-Second Session (Return to Bergenzel!) | Tales to Astound!

Pingback: The Sandbox vs the Railroad… or Spontaneous Story Creation vs. Pre-Plotted Story | Tales to Astound!

I love the CT random tables and their progression and improvement through CT, the Traveller Book and (heresy!) MegaTraveller is noticeable. The sorts of Yoon-son type links you suggest between patrons and actions/targets is quite well handled in the Mongoose Traveller v1 tables. This shows the living use and utility of these procedures, for Traveller at least, through the 80s and even the 00s. This is in contrast with mainstream RPG culture as you outline in the article above.

Pingback: #RPGaDay 2017 – Which #RPG do you prefer for open-ended campaign play? – Bravo Zulu

Once again, this is spot on. I’ve mentioned in other places that the pre-1980 RPG hobby I was familiar with tended to view “canned adventures” as something you did if you didn’t have time to come up with your own stuff. Random tables were seen as being a spur to the imagination, which is something you can see quite readily in the earliest Judges Guild Journals (larger newsprint edition). Traveller was clearly a framework for running games reminiscent of Tubb, Vance, Anderson, Dickson, Niven & Pournelle, Le Guin, and the like – but you got to decide what it was going to be. The Third Imperium came later.

The Random Encounter tables are a solid starting point for, as you say, certain expectations. If you read some Dumarest, Vance, Anderson, et. al, and then look at the Patron Encounters Table there is, without doubt an “Ah-ha!” moment. (Back when I first read Traveller, my SF reading consisted mostly of Asimov, Heinlein, Ellison, and Herbert, so I didn’t “grok” the Patrons as a direct line from SF fiction at first.)

The value of looking at something like Yoon-Suin, as noted in the post above, is that one can make encounter tables specific to the setting the Referee creates.

The tables can be established for, say, a subsector, or specific worlds. The Referee daydreams, “What sort of aliens…? What sort of society…? What sort of social problems…? What sort of drives and motivations…?” … are common to *this particular interstellar society/chunk of space???”

Absolutely. One aspect of this is realizing that the encounter tables in OD&D are _guidelines_. When Greyhawk came out, there were new encounter tables provided, but by Blackmoor and Eldritch Wizardry, it became clear you could do this for yourself – and should.

The one element lacking from the tables in Worlds and Adventure is a “reason for hiring” table for patrons – which is what the Yoon-suin tables and your additional examples quite clearly demonstrate.