This post on personal combat in Traveller Book 1 generated some great comments both in the comments section, but on several other sites across the Internet.

Over at the G+ Classic Traveller community a solid conversation took place inspired by the post. Because we covered so many ideas and topics, and the nature of the conversation revealed people sorting out ideas (including myself) I thought I’d share the thread directly, allowing people to see how the ideas flowed.

Also the group is great. And if you are interested in Classic Traveller you should check it out.

Michael Thompson

Close combat with someone who has a clue with a firearm should be deadly in short order. I was part of the security response force aboard a submarine, and we stressed the importance of finding cover and concealment, and gaining surprise.

Christopher Kubasik

+Michael Thompson I think something that can throw people off about the original Traveller combat rules is that they want RPG combat to feel like … well, RPG combat. They want lots of rounds, a slow ablative decay of hit points, and durable PCs that have time to take stock of a battle that is going south and change tactics accordingly.

Marc Miller was a captain in the army and, believe, served in Nam. He wrote the rules to reflect how he saw a firefight would go. And so the game has rules that are brutal, quick, and dependent on the Players/PCs being smart long before the bullets start flying.

Jeff R.

Another excellent post. Something to consider is that, RAW, movement is normally completed before combat throws, so it would be possible (subject to Ref judgment) for the PC under fire to “evade into cover” before the combat throw is adjudicated, or maybe even “close range” from Short to Close. In the end I find CT combat fast, furious and fun, to steal a tag-line from another game.

Christopher Kubasik

+Jeff R. Yes! I implied that in the post, but didn’t spell it out. I should probably fix that.

Daniel M

At a past GenCon I ran a session in which a player, armed with a dagger, attacked a Stormtrooper in combat armor. After the dagger attack failed the trooper opened up on the player with his laser rifle and scored a hit. Everyone at the table knew that character was a goner. I picked up 5 dice, shook them, and dropped them in the middle of the table for everyone to see. 1, 1, 1, 1 and a 2. The player barely noticed the injury and the rest of his party toasted the trooper with their own weapons.

Hitting your target is only the first part of the story.

Jeff R.

+Daniel M Ha! I had something similar happen in my home game, where a foil-wielding Marquis charged an Auto-Pistol armed kidnapper and not only didn’t get hurt, but disarmed the cad…

Alistair Langsford

+Christopher Kubasik You’ve written a lot of good stuff on CT, but I think this might be the best article so far. CT and its combat always seemed to be a stumbling block with various groups when I was just getting into RPGs. But not the group I started with, of whom I and one other person out of about 8 were the only ones who didn’t have military and/or wargames experience. They had quite a different view from the rest of the roleplayers I gamed with.

I think one of the key reminders you make is that PCs are awesome when it comes to firefights. A fact many forget. But, to steal a quote from one of my favourite action movies, they’re still ‘Touchable’.

Jeff R.

Another excellent post. Something to consider is that, RAW, movement is normally completed before combat throws, so it would be possible (subject to Ref judgment) for the PC under fire to “evade into cover” before the combat throw is adjudicated, or maybe even “close range” from Short to Close. In the end I find CT combat fast, furious and fun, to steal a tag-line from another game.

Christopher Kubasik

+Jeff R. Yes! I implied that in the post, but didn’t spell it out. I should probably fix that.

Daniel M

At a past GenCon I ran a session in which a player, armed with a dagger, attacked a Stormtrooper in combat armor. After the dagger attack failed the trooper opened up on the player with his laser rifle and scored a hit. Everyone at the table knew that character was a goner. I picked up 5 dice, shook them, and dropped them in the middle of the table for everyone to see. 1, 1, 1, 1 and a 2. The player barely noticed the injury and the rest of his party toasted the trooper with their own weapons.

Hitting your target is only the first part of the story.

Jeff R.

+Daniel M Ha! I had something similar happen in my home game, where a foil-wielding Marquis charged an Auto-Pistol armed kidnapper and not only didn’t get hurt, but disarmed the cad…

Frank Filz

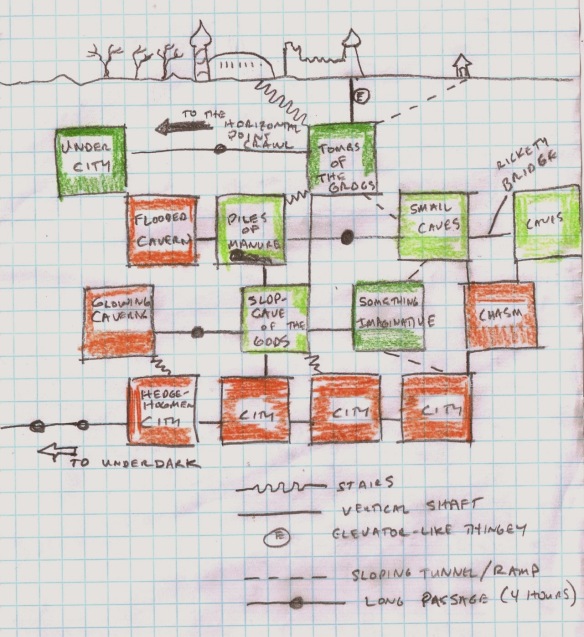

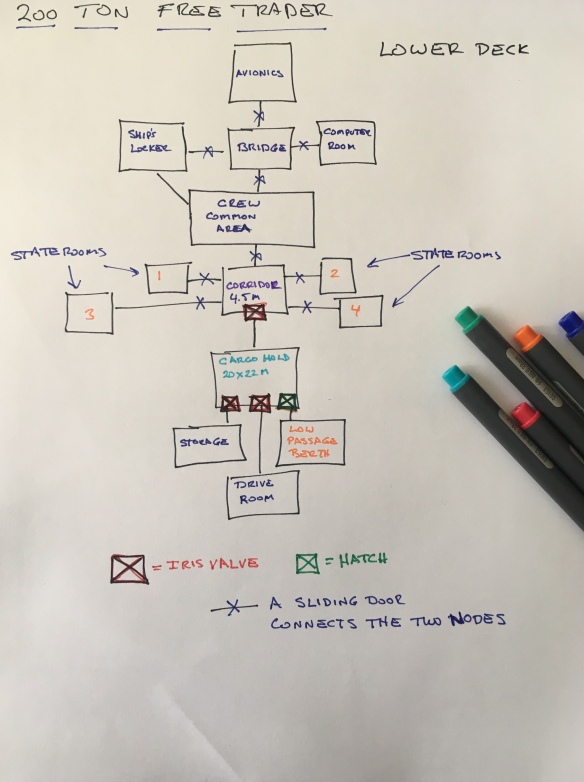

Great post. There’s a reason in Daniel M’s game when we were intercepting a ship, I had my character who had Vacc Suit-2 and Shotgun-3 EVA and come in through a different airlock (and note that a standard Traveller vacc suit counts as cloth armor). It should also be noted that the shotgun lets you hit multiple targets also… And it’s allowable at a higher law level than any other firearm…

Oh, and that Shotgun-3 skill, two of those skill levels came from mustering out…

Christopher Kubasik

+Alistair Langsford, this is a really solid point — which I made in the post but I think is worth reiterating here:

“AWESOME only in the sense of having that zero level Often people seem to complain that CT characters are limited and can’t do much and are somewhat fragile in fights. Not quite so. ON the other hand PC choices are sometimes less than awesome.”

The fact is once you add in the DMs for range, armor, and bonus or penalties for high or low characteristics, the skill level often becomes a relatively insignificant part of the calculation to hit that 8+.

Of course, most people in the world of Traveller have no combat training (not firing range training, but combat training) and so suffer the – 5 DM when using a weapon. In this regard, the PCs (with a default expertise of 0 or even skill levels) are definitely better than most folks — and so are awesome by comparison.

That most people pick up the rules, focus only on the skill rankings of a PC, and miss all those DMs for range, armor, and characteristics is caused by many reasons.

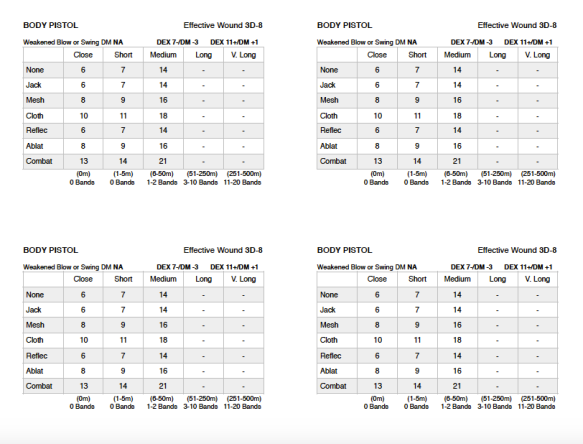

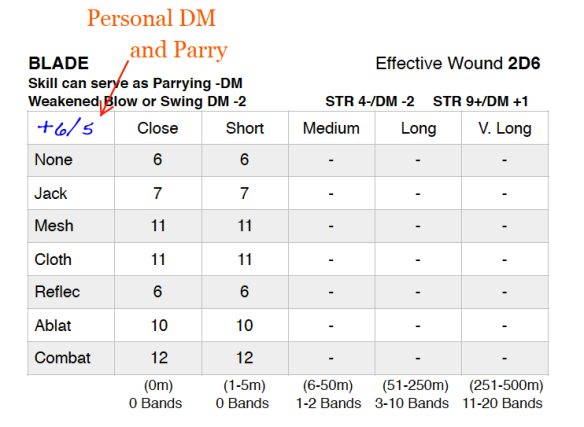

I suspect that one of them is that the combat DM matrixes split up the DMs for combat and thus makes it hard to see how the DMs will play out in a clear manner. A person sees those two matrixes, kind of gets hypnotized by all those numbers swimming around on the page that combine into something but it’s hard to see clearly unless you write it all out.

This is one of the reasons I made the weapon cards: I wanted to be able to see clearly what each weapons was going to be able to do in different circumstances. And I wanted my players to be able to see it clearly, too.

Christopher Kubasik

+Jeff R. This is an important point:

“Another excellent post. Something to consider is that, RAW, movement is normally completed before combat throws, so it would be possible (subject to Ref judgment) for the PC under fire to “evade into cover” before the combat throw is adjudicated, or maybe even “close range” from Short to Close. In the end I find CT combat fast, furious and fun, to steal a tag-line from another game.”

I want to think more about this because, of course, the NPC can move at the same time as well. He can be trying to cut the PC running for cover off, or try to get to a better flanking position if he sees the PC might try to evade into cover.

This matters because of something I have never thought about before, but I’m going to give it some thought: Since all movement is simultaneous and all firing is simultaneous, when does the Referee decide what the PCs will do? How does he decide it?

Does he write it down on paper before the PCs/Players declare movements? Does he let the PCs/Players declare first and then roll a die with two or three possibilities and randomly determine which action he takes, with different odds, perhaps for different actions?

Again, I’ve never thought this through, but I do think it is worth thinking about, as it will determine how the Player feel the combat system works, if they’re enjoying it, and can help layer tension and excitement depending on how choices and actions are revealed.

Frank Filz

Back in the day, when playing RPG systems with simultaneous action in combat, I always had the players make their declarations. I would have some idea what the NPCs/monsters would do before they made their statements. Reasonable reaction to other statements was acceptable (like changing where you moved if an NPC or other player made a movement that might impact what you were doing). While I did not have exposure at that time to Free Kriegspiel, I think the way I handled simultaneous action fits well with that philosophy. I rarely had complaints from players so it must have felt natural to players (even ones with no previous wargaming experience).

In fact, watching some play of Metagaming’s Melee turned me off of initiative systems (a fast enough character could move behind an opponent and strike from behind, without the opponent having any ability to turn as the guy was circling around him).

This issue also made me wary of explicit facing (and in college, the Cold Iron game a friend developed that we played a lot had a further issue with facing and such. We usually used a hex grid for combat, but only 4 people could attack one opponent, so how do you resolve things when 6 opponents can fit around you on the board… In the end, I had written up a house rules document that laid out combat in more detail as our play developed more in the “board game” direction in the same vein as D&D 3.x.

And with all of that in mind, for my Classic Traveller play, I will allow myself to be informed by Snapshot but I won’t directly use it, keeping combat more free form (but not entirely theater of the mind – I’m ok with using a map and a grid, but we won’t always count squares or hexes).

Daniel M

+Christopher Kubasik I have to disagree with your statement “the skill level often becomes a relatively insignificant part of the calculation”. With the bell curve of two six sided dice being so short a single +1 DM from skill level can make all the difference. See my previous posting “The Power of ‘1’”.

Jeff R.

+Christopher Kubasik I don’t use a methodical decision tree, I just have an idea what the NPCs will do, go around the table asking for actions (e.g., “I dive for cover, shooting the nearest kidnapper”, “I spray my gauss rifle across the largest cluster of thugs”, etc.). The players don’t always use the “evade, close range, open range, stand” options when stating movement, though usually it’s obvious, or I ask for clarification. When it comes to combat throws I’ll sometimes decide, sometimes roll to see if shots went off before someone reached cover, depending on circumstances. I’ve resisted trying to add anything more formal, and so far it has worked just fine.

Christopher Kubasik

Hi +Daniel M, I don’t think we are disagreeing. Please note that I’ve been banging the drum to get people to understand that a skill-1 is actually a big deal in Classic Traveller 2D6 bell curve for some time now.

What I think we need to focus on in the statement you quoted is the word “relatively.” For example, someone shooting at a unarmored target at short range with an SMG is going to get a DM +5 for firing at target not wearing armor and a DM +3 for firing at a target at Short range.

For armor and range DMs alone the shooter has racked up a DM +8. Obviously on a 2D6 bell curve this is an enormous advantage. So much so that on a Throw for an 8+ to hit the PC cannot miss.

I’m not saying the SMG-1 rating the shooter poseses doesn’t matter. I’m saying that in the situation described above it matters relatively less than other DMs. In this case a PC is going to have the same odds of an effective hit whether they have SMG-1 or SMG-0.

Which was the only point I was making. Skills matter, but they are not all that matters. But people, for whatever reason, really focus on the skills and their levels when reading the Classic Traveller rules.

Christopher Kubasik

+Jeff R. Do the players find out what the NPCs are doing before or after they declare actions? (Or is it a mix of some kind?) That’s what I’m curious about.

Because if you close range to get to melee and I open range with a firearm while you charge me you might get caught out in the open at short range and I get a shot off on you. That’s going to matter!

And I agree with pretty much everything you and +Frank Filz have written about keeping it simple.

Frank Filz

So if you declare backing off to open range, and my guy is trying to close with you, then we look at relative movement rates (they may be the same) and you probably get a nice shot off. It’s also hard to judge these things in abstract scenario, once in play, we have more information to make an adjudication with.

Todd Zircher

True, true, and backing up probably means that your opponent has been flushed from cover and is open to all kinds of other hurt. 🙂

Christopher Kubasik

Yes. The part about relative movement rates I understand.

I am trying to figure out the best order to decide/reveal the NPC’s choice to open range.

If i’m the Referee it might not occur to me to have the NPC back up until the Player announces his character is going to charge. But if actions are simultaneous should I be making decisions based on foreknowledge of the PCs’ movements?

If I’m the Player I might decide I don’t want to charge if the NPC is going to back up and leave me exposed to a shotgun blast at short range.

It seems to me that a) when actions are announced and b) when characters are committed to actions matter. And I’m thinking that through.

Jeff R.

I see the issue: I run a loose game where the PCs are of heroic stamp, and they always get the benefit of the doubt. But I do decide what the NPCs are doing before asking the players, and if the NPC actions might change what the player wants to do I generally give them a chance (Saving Throw) to change, as long as the change isn’t too drastic. The NPCs never get that chance, since the story isn’t about them.

Frank Filz

+Christopher Kubasik Yea, totally. Players can make their statements of intent conditional which helps. If the player was trying to decide whether to break cover to close and the NPC was going to open range, I think either the NPC’s intent would be clear to the PC before breaking cover, or it would be more the case of the NPC backing up in reaction to the PC breaking cover.

If it really became an issue, I’d possibly call for some kind of random throw to determine who gets to react to whom (note that many initiative systems actually leave the more reactive character committing first which can seem backwards – another reason to use common sense rather than a strict procedure).

Again, I think in the moment of play, there would be more information than our cooked up scenario to help decide what happens. That doesn’t mean talking and theorizing isn’t helpful in opening our eyes to different ways to interpret the situations we face in play.

Christopher Kubasik

+Frank Filz That all seems reasonable to me. I’m a big believer in “Let the fiction sort it out.” And my first post on this issue above suggests exactly what you suggest — if I’m not sure which way an NPC will go, I’d come up with a random die roll to determine a course of action.

Whether this is “theorizing” I have no idea. (Well, that’s not true. I certainly wouldn’t consider it “theorizing.”) The rules offer no instruction on how to handle this stuff. And my thesis for the Out of the Box posts has been that many of us have been “trained” to play a certain way — and that Classic Traveller works from assumptions counter to most other RPGs. By naming specific issues at hand in apply the Classic Traveller rules the would-be Referee can visual and imagine ahead of time how the application of rules might work out.

(As a side note: I think that in many ways Vincent Baker’s Apocalypse World is closest in spirit and application to games like Original D&D and original Traveller. One will note there is no initiative in AW as well, and the fiction finds a way…)

Alistair Langsford

+Frank Filz When I think about the rules, I think I have many of the same issues as +Christopher Kubasik mentioned when it comes to “simultaneous”. Mainly because of my experience from other games where you have to write your moves so the declarations as well as resolutions are simultaneous. When I’m gaming it I realise it often has come down to more of what you and +Jeff R. describe: order often becomes obvious. And we’ve forgotten to “roll for initiative” because tho’ we initially started with Mongoose Traveller we seem to have ended up running pretty much CT. I think I’ve been overthinking it. And, this isn’t a war game. I think you’ve all helped me get a better idea on how to run CT combat. Thanks.

Victor Raymond

Generally speaking, that’s why initiative has mattered in other game systems. Not that it allows someone to go first, it’s a matter of “are you acting, or reacting?” In a wargame, if you win the initiative, you have two choices:

1. Move and act first, attempting to gain an advantage before your opponent can stop you, or

2. Wait to see what your opponent does, and then act.

In either case, rules about movement and engagement model the consequences of your actions, and depending on your resources, your decision could affect the rest of the battle. A lot of this may seem abstract, but even on the 1:1 scale of CT, that’s what those bonuses for Tactics, Leader, and prior military experience model in the surprise roll.